The Persistence of Gender Stereotypes in Tech

In the dynamic world of technology, it’s crucial to address the challenges faced by women in their pursuit of successful careers.

Gender stereotypes in the tech industry are deeply ingrained in our society and continue to shape the subculture of technology. Statements like “Women aren’t good with computers” or “STEM is for nerds” are not only misguided but also reinforce biases that limit diversity and inclusion in the field.

To truly address these issues, we need to understand their origins and work towards a specific approach to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) in tech. Let’s dive in.

The Past: Women in Computing

Let’s start with the origins of computer programming. Did you know that throughout the 60s, women programmers were the norm?

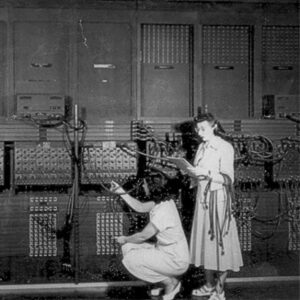

In 1967, Cosmopolitan magazine even published an article titled “The Computer Girls” – a reference to the women working with ENIAC considered to be one of the first electronic, digital computers – recommending their readers pursue a computer programming career.

According to Mar Hicks, author of the enlightening book “Programmed Inequality,” women held the largest share of technical expertise in the computing industry during World War II and continued throughout the mid-60s. They were managing and operating enormous room-sized electromechanical computers, cracking codes, and formulating military strategies. These talented women then transitioned into working for civil service departments, proficiently handling data and software.

Now, there’s a catch. The work itself was perceived as handicraft as opposed to intellectual and the women operating the system were known as ‘operators’ or ‘coders’, not software developers. One piece of pretty outrageous fact is that the six women, whose software work was critical to ENIAC’s operation and performance, did not receive an invitation to the celebratory dinner for the completion of ENIAC. Yes, you read that right.

However, despite the less-than-ideal conditions, women were at least present in the field. So, what happened? How did we go from a sector that was largely built and operated by women, with almost a 50/50 gender split, to a dismal 37% by 1986, and a measly 26% of the total computer science workforce today?

The Shift: From “Computer Girls” to “Brogrammers”

Originally, men specialised in hardware engineering – building circuits and machinery – women were in charge of building software. However, with the onset of the Internet Age from the late 60s things began to shift. Once companies saw the potential for software to change the game, the demand for skilled work increased.

The first problem was that no one really understood what skills were necessary for this “new” field. Programming was essentially seen as somewhat of a ‘black art’, and companies started to believe programmers were ‘born, not made’.

Then for industry giants to be able to recruit fast enough and meet the demand of an unknown growing sector, the simplest answer involved recruiting programmers through the use of aptitude tests. The tests were designed to filter for traits that related to analytical thinking and abstract reasoning.

According to Ensmenger, by 1962 a whopping 80% of businesses had begun using aptitude tests as a means of hiring skilled programmers. Half of which used IBM’s industry-standard PAT (Programmer Aptitude Test). In 1967 alone, More than 700,000 individuals had taken the PAT. The test had become the gateway for budding programmers interested in pursuing a career in the field.

As the demand for programmers continued to increase, companies soon realised aptitude tests were not enough to identify specific personality profiles that make for motivated and effective programmers. System Development Corp (SDC), hired by IBM in the 50s to work on the SAGE – one of the biggest software projects of the time, was one of those companies. What they decided to do, changed everything.

The biased and misguided study that changed everything

To streamline their recruiting process, SDC had commissioned two psychologists, William M. Cannon and Dallas K. Perry, to pinpoint a “vocational interest scale” for programmers. In 1966, Cannon and Perry interviewed 1,400 engineers (1,200 being men) and developed a personality profile to predict the best potential candidates. What they found bore a resemblance to other vocational profiles for chemistry and engineering. However, there was one notable characteristic attributed to programmers: Disinterest in people.

Given their largely male-dominated test group, Cannon and Perry’s assessment disproportionately identified men as the ideal candidates for computer programming jobs. In particular, the vocational profile test tended to eliminate extroverts and people who have empathy for others. Two common traits that were stereotypically attributed to women.

profile test tended to eliminate extroverts and people who have empathy for others. Two common traits that were stereotypically attributed to women.

So there you have it. This misguided study laid the foundations for the ensuing male anti-social coder stereotype of the “geek” or “brogrammer” was born.

By the late 1960s, the ‘soft work’, which had been largely dominated by women, evolved into modern software, and the importance of women decreased. Once the industry grew more lucrative, and it became clear that those who knew how to utilise software were at an advantage, female programmers lost out despite having extensive experience and the requisite skills.

SDC’s programmer profile came to shape industry demographics for decades. This pivotal study changed forever the way companies recruited and trained programmers, and impacted the tech industry’s ability to be diverse and inclusive ever after.

How did this impact the future of women in tech?

As time went on and the industry continued to turn a profit, male executives developed hiring criteria and workplace cultures that systematically sidelined women. Rather than creating a space that empowered women, the education system and business structures helped to reinforce masculine biases and patriarchal norms.

In schools and universities, boys were encouraged to study maths and engineering, while girls stuck to the social sciences. Then by the early to mid 1980’s, video game consoles and personal computers hit the market, and were marketed as “boys toys”. Even today, we still hear the same false messaging being thrown around such as: “Technology is designed for boys, not girls”.

This study contributed to shaping the way our society thinks about people working in technical fields, making everyone wrongly believe that biology has anything to do with one’s ability to work in STEM. Clearly, the early history of programming, all the hidden women in the history of science (more about them in upcoming posts, don’t forget to follow us on socials), and the highly successful women currently in this field prove the above preconception is ludicrous. Unfortunately, dismantling gender stereotypes and biases takes a while.

What can we do to break the vicious circle and achieve gender equity in tech teams and the tech industry?

A lot! It could be the topic of an entire other blog, but here are some highlights:

- Accelerate Career Advancement: Invest in the career development of women in tech by providing mentorship programs, opportunities for skill-building, and ensuring a fair promotion process.

- Equal Pay: Eliminate gender pay gaps and promote pay transparency to ensure equitable compensation for all employees.

- Equal Parental Leave: Implement policies that support equal parental leave, recognising the importance of work-life balance for both men and women and avoiding gender biases in family-building responsibilities.

- Inclusive Hiring: Review and revise hiring processes to ensure they are inclusive and free from biases. Adopt blind resume screening, diverse interview panels, and inclusive job descriptions to attract and retain diverse talent.

- Inclusive Workspaces: Create inclusive work environments that challenge stereotypes (no dark programmer corners with no lights, no plants, no colours lol) Encourage comfortable and inclusive office spaces that promote collaboration and well-being.

- Support Girls in STEM: Partner with organisations and initiatives that encourage girls to pursue STEM education and careers. Provide mentorship, internships, and awareness programs to inspire and guide young girls.

These are just a few actionable steps that can make a significant difference in promoting diversity, equity, and inclusion in tech. Embracing diversity not only aligns with core ethical values but also brings tangible benefits to businesses, including increased innovation, improved problem-solving, and enhanced productivity.

Ready to do more and remove systemic barriers for women in tech? Look into the Project F certification programs or start by evaluating where your company stands with our Pulse Check.

And if you’re a startup, Project F has the perfect cost-effective solution that will enable you to easily weave DEI into the fabric of your business for sustainable outcomes! Check out our Gender Equity Toolkits here.